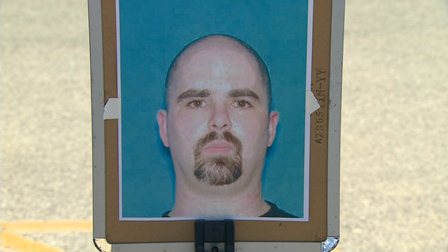

(CNN) -- When Wisconsin temple gunman Wade Michael Page arrived at Fort Bragg in 1995, the sprawling Army base in North Carolina already was home to a small number of white supremacists including three soldiers later convicted in the murder of an African-American couple.

(CNN) -- When Wisconsin temple gunman Wade Michael Page arrived at Fort Bragg in 1995, the sprawling Army base in North Carolina already was home to a small number of white supremacists including three soldiers later convicted in the murder of an African-American couple.

The killings launched a military investigation that tightened regulations against extremist activity, but some say such influences persist in today's armed forces.

"Outside every major military installation, you will have at least two or three active neo-Nazi organizations actively trying to recruit on-duty personnel," said T.J. Leyden, a former white power skinhead in the U.S. Marines who now conducts anti-extremism training.

Page died in a shootout with police responding to his attack Sunday on a Sikh temple in the Milwaukee suburb of Oak Hill that killed six people and wounded four, including a police officer.

He had ties to white supremacist groups and the FBI acknowledges it knew of him, though no formal investigation ever took place.

According to Pete Simi, a University of Nebraska criminologist who knew Page, the military experience at Fort Bragg helped instill Page's allegiance to the white power movement.

"What he told me during the course of our time together was that he really started to identify with the neo-Nazism during his time in the military," said Simi, who met Page in 2001 while doing a study on white power groups in California. "And specifically, what he told me at one point was that, if you join the military and you're not a racist, then you certainly will be by the time you leave."

In particular, Simi told CNN, Page's military experience bolstered his perception that "the deck was stacked against whites."

"He came to feel that there was preferential treatment for African-Americans in the military and whites were always on the short end of the stick," Simi continued. "And the more he got into the Nazi ideology, the more he came to see all of society in that way."

While Page knew about neo-Nazis and racist skinheads before joining the Army, "he really started getting into it during his time in the military," said Simi, author of "American Swastika: Inside the White Power Movement's Hidden Spaces of Hate."

Page joined the Army in 1992 and ended up at Fort Bragg in 1995, around the time that the base became the focus of white extremism in the military when three members of the 82nd Airborne Division stationed there were arrested in connection with the murder of an African-American couple in nearby Fayetteville.

Investigators found neo-Nazi materials in the barracks of the men, and all three were eventually convicted. The case prompted a military review that determined 22 soldiers at the base had past or present links to skinhead groups, though investigators concluded there was no organized extremist movement operating among the more than 14,000 troops of the 82nd Airborne at the time.

Those who served with Page say he showed racist tendencies then.

"He was involved with white supremacy. He talked about the racial holy war a lot," said Chris Robillard, who met Page at Fort Bragg in 1995 when both were doing psychological operations training.

While describing Page as a close friend and a kind person, Robillard also said that "when he'd rant, it would be about mostly any non-white person."

"I know everyone is going to paint him as a racist with hatred, but that's not how I remember him," Robillard said. "The racial holy war talk I always took as something he would vent about, and not act on it. I never pictured him as someone who would do anything. I thought maybe he was just saying it for attention."

To J.M. Berger, a counterterrorism analyst and editor for IntelWire.Com, the military attracts extremists because of the weapons training it provides.

"One thing that we really have to keep in mind is that extremists are often explicitly interested in joining the military because they get training that they can use later," Berger told CNN, adding that "there have been some explicit discussions among leaders of some of these groups that their followers should join the Army to get trained."

In talking to military veterans, Berger said, he hears "different things from different people."

"Some say that there's not a massive problem. Others have expressed concern to me about what they've seen in the ranks," he continued. "And, you know, the military is a massive operation like the U.S. population. There are going to be some people who are problems."

Page received a general discharge under honorable conditions from the Army in 1998 due to "discreditable incidents," according to a Pentagon official who spoke on condition of not being identified.

Robillard said Page showed up drunk for duty one morning, which led to his eventual discharge. The two men parted ways until 2000, when Page visited Robillard at his home in Arkansas.

"He had gone through a dramatic change," Robillard said of the meeting, the last time he saw Page in person. "His talk about the racist war was ... more like he really did believe it."

Leyden, the former white supremacist who wrote the book "Skinhead Confessions: From Hate to Hope," said he openly displayed his extremist leanings while serving in the Marine Corps in the late 1980s.

"I used to hang a swastika flag on my wall locker and everybody in my unit all the way up to my commander knew it," he said. "The only time they ever asked me to take it down was when the commanding general would come through, just so they wouldn't get in trouble. And afterwards, I would put it right back up and they were perfectly fine with it."

He noted that his brother's unit had less tolerance for such displays.

"His commanding officer went to the barracks and anything that was racist or seemed to be racist, he made them send it home," Leyden said. "So it really depends on the commanding officers and who's in charge of that base."

After the 1995 murder case involving the three Fort Bragg soldiers, the Army appointed a task force to investigate the extent of white supremacists in its ranks and also started including training against extremism.

According to the Department of Defense website, the task force visited 28 installations and interviewed more than 7,500 soldiers. It found that less than 1% said they had seen soldiers or civilian employees involved with extremist groups.

A decade later, the Southern Law Poverty Center reported in 2006 that some high-profile members of extremist groups were serving in the U.S. military.

According to the organization, which tracks hate groups in the United States, the presence of extremists in the military increased with the need to bolster ranks for the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

- Home

- News

- Opinion

- Entertainment

- Classified

- About Us

MLK Breakfast

MLK Breakfast- Community

- Foundation

- Obituaries

- Donate

11-25-2024 5:35 am • PDX and SEA Weather